10 years after the release of his 2011 film Like Crazy, director Drake Doremus opens up about the making of the film, the impact Felicity Jones and Anton Yelchin had on his life, the original ending, and more.

Art tends to find us when we need it the most. For some, it’s a monumental album with lyrics that speak directly to one’s soul or the prose of a book that lingered much longer than any other. For 19-year-old me, it was Like Crazy. The film, which was co-written and directed by the then-27-year-old Drake Doremus and buoyed by performances from acting powerhouses Anton Yelchin and Felicity Jones, Like Crazy is the semi-autobiographical film inspired by Doremus’ real-life experiences with first love and a long-distance relationship. The premise is simple: a British college student named Anna, played by Felicity Jones, falls in love with an American classmate named Jacob, played by the late Anton Yelchin, and overstays her visa when studying in America, naively believing it’ll be a simple fix. What follows is an exploration of love, the lengths we go for it, and, at its core, how the pieces of ourselves we leave in one another never just simply fade away.

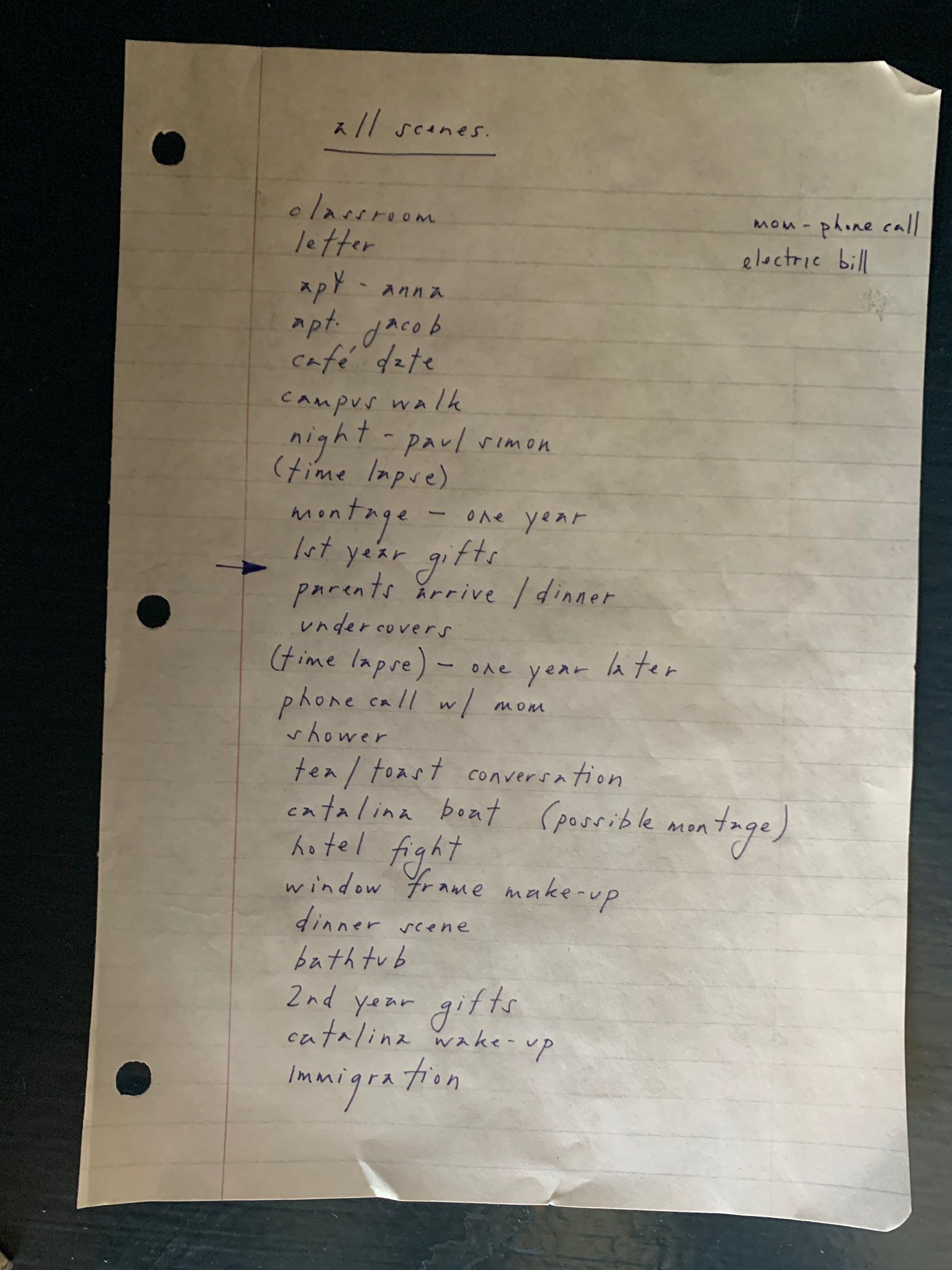

After its premiere at Sundance, Like Crazy received critical acclaim and won the film festival’s 2011 Grand Jury Prize, praising Doremus for his deft direction and the performances of Yelchin and Jones. 10 years ago today on October 28th, 2011, the film had its highly anticipated limited theatrical release across North America where audiences like myself found themselves floored by the ease in which Doremus allowed both actors to merely exist in the scene, improvising the entire script for conversations to flow naturally and organically rather than plague them with sticking to a script that had heavy, wordy dialogue.

By working in this manner, Doremus created a film that is both timeless and universal, easily relatable to anyone who has loved and lost or, like the then-19-year-old me, never even experienced love at all. Despite the modest budget and simplicity of the story, Like Crazy still has the same impact as it did a decade ago. When scrolling Twitter or reading reviews of the film posted as recently as yesterday, audiences grapple with trying to grasp the appropriate words to explain why the themes and messages woven throughout the film matter so deeply to them.

1883 Magazine’s Kelsey Barnes chats with Drake Doremus about the film’s influence after its release a decade ago, what it was like working with Felicity Jones and the late Anton Yelchin, unique anecdotes about the movie, and more.

Congratulations on 10 years of Like Crazy. Firstly, can you believe it’s been a decade and what is it like to be looking back on Like Crazy now ten years later?

It’s really strange, to be honest. Everyone’s gone to do so many different things in their lives since Like Crazy so when you think back to that time, it’s more about how much has changed. People have had babies, they’ve grown up, they’ve pursued different things. It’s bizarre in some ways; it doesn’t feel like it was 10 years ago and in other ways, it feels like it’s been 30! [Laughs]

As a viewer, I feel the same. I saw it for my 19th birthday in 2011 and it’s been interesting to reflect on how I’ve grown and experienced things in Like Crazy that I didn’t think I’d ever experience. To prep for the interview, I rewatched it a bunch and I picked up on things 19-year-old me didn’t notice, like the way money and wealth are subtly hinted at. It’s a totally different viewing experience for me now. How has it changed for you, both as a writer & director and just as someone watching it?

You’re right, it does change as you grow up. I actually haven’t seen it in nine and a half years. I don’t watch my movies after I make them; I go to the festival where the premiere is at and I’ll watch it with an audience once and never see it again. It’s as if it’s no longer mine anymore; you have to give it away for someone else to enjoy and allow it to become theirs.

With Like Crazy, I think about everything except the movie. I think about Anton [Yelchin], I think about Felicity [Jones], I think about the amazing time and connection we were able to share. It was this moment in time where we came together to make this thing. That’s what I remember when I look back on the film and how it’s grown. I know how I was feeling and where my heart was at that time and why I felt it was so important to tell that story. I’m sure if I watched it today I would cringe and want to change everything. I like thinking that it, and all of my movies, are just a moment in time and then they are gone.

When the film first came out, journalists were somewhat obsessed with it being a semi-autobiographical film and I believe you said to IndieWire that you were crying every day while writing and shooting it. Although your past films carry the same emotional weight, Like Crazy in particular always felt like a diary entry from you.

It really was, it was an emotional time going through the longest relationship I’d ever have at that point. I was feeling all of these things and wanted to tell the story in a way that wasn’t blaming anyone, but just encapsulate the experience of what I felt in my heart. I was just trying to be as honest as possible. I was living with my dad at the time and I edited this tiny little movie in the guest bedroom and it was such a personal experience where I never really thought about people seeing it.

When I was creating it with Ben [York Jones] it was an insular experience; we were just trying to be honest without feeling like we had to prove something. We both were going through similar things and it was a way for both of us to process our emotions. It’s a dream come true to share your experiences and emotions with the world and have people react and let you know they’ve experienced the same thing. You feel connected and that’s what is so special about film and art in general; we connect through these forms and realize we are all connected and sharing a universal human experience. The things we do affect one another and mean something to each other. That’s the best and most profound thing anyone like me could experience.

I agree. I was searching the words “Like Crazy” and your name on Twitter and there are still people who feel deeply moved by this film and that shows that what you created is timeless because everyone has experienced something similar.

You’re so right! That’s the weird thing–when I was making it, I thought that it was such a specific experience that not a lot of people have. Now I know that so many people over the world have had long-distance relationships for one reason or another, whether it’s studying abroad or meeting someone when travelling. So many people have told me that I’ve told their life story which means a lot to me. It’s amazing how many people have had a long-distance relationship and can relate to the movie, both are totally unexpected things. When you’re 26 years old, you don’t go around polling people to see if they’ve had a long-distance relationship, you just are in your own little bubble of emotions. It’s made the entire experience full circle for me.

Which is interesting when we think about the film in regards to the pandemic because I know last May you posted about it being 10 years since you started making it and you were reflecting on that time. Obviously, the pandemic forced everyone to be away from their loved ones in a different way. What was it like to be revisiting those memories during the pandemic?

I was thinking a lot about Anton who we still miss very much. In the pandemic, everyone had their little circle over the summer and realizing that he was not a part of that was still very emotional for me. It was just a reflective time to look back and remember when we were making it. We ran over to London with seven people and shot on the streets and made our little movie. It’s bizarre to think you could do that today. Things have changed so much and the industry has changed so much, the film is definitely a product of its time. I kind of like that you can’t just recreate all of the lucky and amazing things that fell into place for us to make Like Crazy. That’s mostly what I was thinking about last year.

I love that you say it’s a product of its time because when I was watching it this week I noticed Anna has a flip phone at the start and eventually transitions into an iPhone. I love the subtle nods to the passing of time.

God, it’s amazing to think people had flip phones in 2010! I’m sure the iPhones in the movie look incredibly archaic compared to today.

And you shot it on a regular DSLR camera, right?

Yeah, a Canon 7D with these amazing Zeiss lenses on there.

The camera adds so much to the film, sometimes the scenes are so intimate that it feels like you’re a voyeur. Obviously, you’ve progressed as a director now, but what was it like to make something so detailed on such a modest budget?

I just love that it didn’t matter, you know? Artistry and storytelling are what mattered. I’ve seen stills from it over the years and it still looks great to me despite it being such old technology now. Honestly, I think when you focus on the story and those storytellers who are sharing that story, it’s not about the money or toys or fancy equipment–it’s just a brutally fucking honest retelling that encouraged us every day to seek that truth. Being around people who force you to find your truth and force them to find theirs by digging deeper and deeper and deeper, and then everyone gets to a place where you are both making something special and feeling something special, too. The equipment doesn’t matter, the stories and people do.

When you make a film about long-distance, the places they are set in become a character, too. How has your relationship changed with London and LA since the release of Like Crazy?

[Laughs] Oh my god, it’s so weird. My girlfriend lives in London now so we go back and forth.

I love this, it feels like it’s full circle.

Right? It always comes around. When we shot the movie it wasn’t my first time there, so I’d pass a street or a location that we would be shooting in and it would take me back to that special moment in time. Funnily enough, when I think about London I think about Anton getting a spider bite while in London. If you look carefully enough, he’s kind of limping in the scenes because he got this huge spider bite on his ankle that got infected and we had to send him to the hospital.

Oh my god! I’m going to have to rewatch and see if I can catch it.

Poor guy. He came back and was really leaning into it. I had to ask him if he could basically not limp. [Laughs] He’d just say “Man, I have a huge swollen ankle!” There are just so many funny little moments, especially in London. We became such close friends and family so quickly that the best part is that we were all constantly making each other laugh so making the movie wasn’t as depressing as you’d think. It really was just a group of people that loved and cared about each other making this serious, heartfelt thing.

While I was rewatching it this week, I realized how Anton approaches Jacob with such a quiet, reserved and reflective performance; a lot of what makes Jacob, to me, is by how little Anton actually doesn’t say. My favourite scene of his will always be in Catalina when he’s trying to make Anna laugh.

[Laughs] I love that scene. It’s all improvised so that boat “The Ahi” just happened to be there. That line about saving a cat from a tree once made me laugh so much. I love him in that scene, he’s so genuine and so “him.”

It’s incredible, my friend and I quote it all of the time. You’ve honoured Anton’s legacy in several ways, one of which being Love, Antosha, the documentary about his life. I just wanted to ask you about working with him on Like Crazy because you both clearly had such a bond.

Anton was 21 years old when we started filming which, in retrospect, is crazy, crazy young. Despite his age, he was becoming a man and was really mature, but had this silly side which we got to experience every day. He was so advanced, so far beyond his years. You mention the silence in his scenes and you’re so right–he could do so much with so little. He had such composure, he was so poised, at times it felt like he was a 40-year-old veteran and we were just watching him grow up on-screen.

He was acting for years before Like Crazy, too. Thinking back, he was the opposite of a newbie and brought a wealth of knowledge and skill that he was able to showcase so deftly, especially as Jacob.

He’d been acting since he was a small child so by the time he was 21, he wasn’t actually 21. He had all this experience and knowledge and he was just so thirsty and hungry about life and relationships and growth. He’d be the one who would come to set hours before call time to watch how we were making the movie. He was just so curious about the camera and the process like the cinephile he is. He wanted to be a part of a whole organism that was around him. That hunger and that desire are infectious and it obviously changed my life; I’ll never, ever forget all of the things I learned from him and experienced alongside him.

Let’s talk about Felicity Jones. It would be an understatement to say she’s had quite a career since filming Like Crazy. She ended up winning the Special Jury Prize for her role as Anna. Was there a specific moment during production where you knew you were witnessing something special in particular with her?

From the beginning, her effortlessness was apparent. She was just so smart and so unique and so undeniably special. Every moment just felt like “wow.” Getting them together and realizing there’s something magical going on between the two of them is something I’ll never forget. Right away when she got to LA we just knew she was a unique and special person that isn’t concerned about some of the things actors, especially those starting out, are concerned about when they are trying to break out into the US. At that point, she hadn’t made a movie in America yet but she just went in all in and gave her heart.

There’s a lot of people I’ve worked with where it makes sense when they eventually get to where they do [in the scene] and it took them a bit to learn or blossom, but with her it was immediate. Certain people are famous who don’t deserve to be and she’s the opposite of that. Right away, I knew she was going to have a long career and do whatever she wants.

You guys started filming a week before she booked the role, right?

Yeah, to say she was thrown into the deep end would be an understatement. There really was no time for her to process.

Music also exists as another character in this film. Felicity mentioned in an interview that you gave them a CD to listen to when they were driving around LA and a lot of the music made the final cut. Dustin O’Halloran’s score also gives so much depth to a lot of the scenes, in particular the montages and glimpses of Anna and Jacob’s relationship. We Move Lightly is one of my all-time favourite songs. I’d love to hear about how you and Dustin approached the score and how you chose the existing songs, like Dead Hearts by Stars.

I was listening to Stars a lot at the time, I’d be cutting scenes to it and having it playing while I was working so it just felt natural to include it. With Dustin, I heard his music in Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette and I always felt it was the saddest, most honest music in the world. I was writing to it and we put a lot of his music in just as a temporary thing and a lot of it stayed in. He composed some original stuff and he tried to recompose some of the scenes where the temp stuff was in, begging me to switch it out, but I was just too attached to the old stuff.

Before he even agreed to do it, he came and watched the movie and had to go to the bathroom to compose himself. He was going through a similar experience and everything just felt incredibly real and vivid for him. He knew he had to do the movie and we just bonded over it. He did the score really quickly–I think in 3 or 4 weeks–and we were sending stuff back and forth. It was a really exciting time and a friendship that I cherish very much.

The montages you create are always some of my favourite parts of your films, like the bed scene in Like Crazy, the driving scene in Endings, Beginnings. Is that just a creative choice or something you feel really helps progress a movie such as Like Crazy in regards to the time that passes in the film?

Yeah, montages are big in Like Crazy. It was just an economical choice really more than anything it was just quick storytelling, even if we were able to show it beautifully! [Laughs] For the bed scene, we did all of the day stuff and left the camera there and did the night stuff. It was all done within an hour and a half, just changing the sheets and clothes and setting a bit. It was such a cool, weird way that made sense at the time because we needed to get through that summer very quickly while also showing the progression of their relationship. Rather than having them say something, it made more sense to show that transition visually.

I love seeing the transition of time like at the airport she watches Jacob leave in this baggy army jacket and the next time he arrives at the same airport she’s wearing this proper trench coat, or in her kitchen, she has this ratty old wooden table and the next time Jacob visits she has this new glass table. I loved seeing subtle ways of them maturing and the years that were passing.

We did a lot of that ourselves because we were paying people so little. We lost our costume designer in the middle because she had to go to a movie that was actually paying her so Felicity and I would go to thrift stores and find stuff.

You’re known to allow your actors to improvise their dialogue; you gave Anton and Felicity a 50-page outline that carries more specifics and details and backstory than just a typical script. I read an interview Shailene [Woodley] did for Endings, Beginnings and she discusses how your sets offer a degree of vulnerability that other sets don’t offer because there are so many cooks in the kitchen on studio films. For Like Crazy, a film that rests entirely on the dialogue and interaction between the two characters to show the depths of their love, was it always going to be improvised?

I grew up in the improv world; my mom was one of the founding members of the Groundlings [Theatre & School] and I was always around that stuff. I went to school for more traditional filmmaking but it never felt right. I just started experimenting with hybrid stuff and I realized you actually could have something that evolved throughout 500 takes and see that take 7 was unique in a way that take 10 wasn’t. It can be a totally different film and a totally different experience making it.

If you really understand the intention of the scene and the objectives and emotional beats and essence of the scene, everything else, in the beginning, middle, and end, can change. It feels alive. You’re forcing your actors to listen and actually exist within that scene which more traditional “studio” films don’t always do. Sometimes it feels like the actors aren’t listening to each other, they are just waiting to say their lines and be done with the scene, almost as if one thing isn’t directly affected by the other. That’s what I love so much about making movies this way is that the actors are constantly forced to react and respond genuinely to something as opposed to something they know is going to happen and there’s a big difference. It sparks chemistry in different ways and sparks truth. What you get and find is a completely different version of a human being as opposed to an actor merely acting. The goal is to actually eliminate acting and just let them let go.

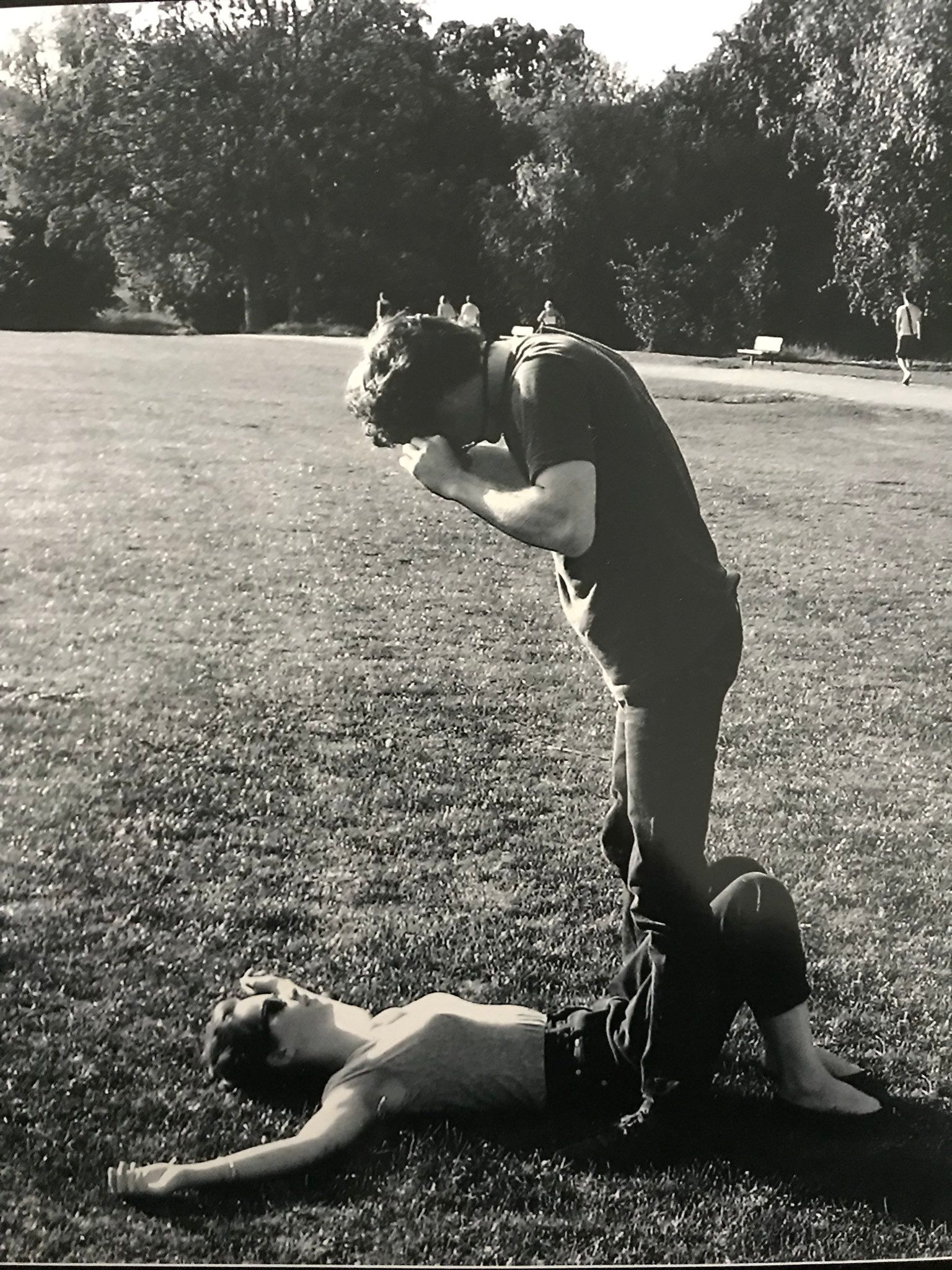

It’s exactly what happens in your films. I know you haven’t seen it in ages, but that scene in the park where Jacob is about to go back to LA and he asks Anna if she’s attracted to other people and she pauses for a second and then says no. Anton immediately picked up on that pause and dove right into it and it added so much to the scene.

That scene is the last we shot and it was in Hampstead Heath. It was actually the last scene they did together. We reshot it because the first one we did on the pebble beach in Brighton and didn’t feel right so we used it in a montage instead. The conversation ended up being in that park, right at the very end of the shooting, and it felt like that is where the scene would actually live and breathe. That was just one of a number of scenes where someone would say just one thing differently and it would change the entire feeling of the scene.

For Anton and Felicity, they were constantly having the same conversations over and over again almost like a real relationship; you’re looping around in circles and not getting anywhere. They would have conversations like that one and we’d just cut it and use pieces of it. For that scene, it’s a cyclical thing; they’re just going in circles with no end, no resolution. It’s just two people trying to dance around this elephant in the room where he knows he’s going back to LA and it’s hanging over them. The way it felt on set is the way it felt when we edited it and put it in the movie.

They only met 5 days before shooting but you did a lot of extensive exercises to get them into the mindset of the characters and their relationship. I’d love to hear more about that process and the exercises you did as it sounds quite immersive.

Great question. I don’t remember the specific places, it was more where it would’ve made sense in their relationship, like where they would go on dates or have fights. We’d build a relationship outside of the structure of the movie so things lived everywhere. It needed to feel like there was a lot of life both between them and behind them so things lived everywhere. We did tons of different exercises at night, too. We rented this old office building for rehearsals and used it from 4-10 pm and would talk about their relationship and the emotional depth of the scene. It was so weird but it felt like it was us against the world.

With the improvisation, were there any lines Felicity or Anton said that made you think, wow I couldn’t have written that.

Wow, there are so many of them. Felicity is a beautiful writer and poet and she wrote the poem Anna reads to Jacob. That was incredibly moving. The scene where Anton talks about saving the cat. Jen [Lawrence] and her line about not sharing bacon is just so Jen, it was great.

I love that you brought up Anna’s piece of writing that she wrote for Jacob, it is some of my favourite prose ever. I’m so happy to hear Felicity wrote it herself.

I wanted her to write it so it was personal between them. I’m not a poet, she went to Oxford, I figured she’d be able to figure it out [Laughs]. I love the idea of giving the actors the agency to become the characters, so Anton learned how to make the chairs and Felicity wrote the poem. It’s just the idea of them immersing themselves in the truth which is really exciting. It’s an incredible poem and it’s perfect for the movie. It came from the inside of her, so it meant a lot, opposed to her being told to say something pre-written by someone else. She really wrote it for him so it had this feeling that something else written for her to say wouldn’t have had the same impact. You just feel that it’s from the heart for her.

My best friend would be mad at me if I didn’t talk to you about the ambiguous ending — I always took Anna leaving the shower first as a sign as she was the one who I felt was always pushing more to get things sorted in regards to her visa. How do you view that scene now?

[Laughs] She might not be happy with this answer! It wasn’t the original ending. My editor Jonathan Alberts showed me two scenes after where they had a conversation out in the living room and he showed me a cut where he asked me to sit with it and not judge it. It ends on Anton in the shower and fades to black. It was so shocking, so abrupt.

With the title card and Dead Hearts playing, too!

Jonathan constructed that whole thing. I sat with it for a minute and knew it felt so bold and said everything we wanted to say at the end of the movie without actually saying it so those original scenes after were just totally extraneous. What I loved about it, and what I still feel so strongly about in regards to the movie, is that this is an ongoing conversation between Jacob and Anna; it’s a grey area that they are always going to exist. I love a grey ending because that’s life, things don’t always end and start perfectly. It’s not how relationships are, so for me, I feel like they’re going to continue having this conversation for years. Maybe they’ll get back together, maybe they’ll break up. It’s like there will always be pieces of them inside one another and that will linger forever. That’s what it feels like with that ending.

Do you have a favourite moment from the film or just from shooting that you keep returning to all these years later?

The happiest I’ve ever been on set was when we were in Catalina and we just finished shooting. It was the end of the first week and Anton, Felicity, the crew and I were on the balcony of that hotel room which we all stayed in during shooting. We were having some drinks and we were exhausted but also exhilarated. We were being fucking idiots and making each other laugh. I remember feeling like we were given the keys to mom and dad’s house while they went for a holiday. I had this moment where I thought, Wow, you can just go work with people you love and have an amazing time and exhaust yourself and then go have fun with them.

I just remember that at the end of the first week I knew it was special and I wanted to cherish that moment together making each other laugh and being silly. I loved talking about what we shot, what could’ve been better, why it was great, or why it wasn’t. It’s just like being in that little family unit. God, thinking back I just remember standing on that balcony and hearing Anton’s laugh. It was just so fucking genuine and when he got going, he couldn’t stop. I just remember feeling like the funniest person alive for a minute. That was the happiest I’ve ever been on set.

Lastly, since it’s the 10th anniversary, what do you hope people continue to take away from the movie even a decade from now?

I hope that for people, whatever they are going through, they know they are not alone. Love is hard but it’s so worth having your heart broken or going through these experiences because you grow up and change. You learn how to be a better human and be a better person in relationships. When you’re young, you think you’re never going to get over anything. It’s so important to go through these things because you think you can’t move on and heal but you always, always do. Hopefully, when people look at the movie whether they’ve gone through something similar or they are about to go through it, I hope they can look back at that moment and know that we’re all humans and all we can do is love. It is cheesy but it really is better to love and lose than to not love at all. It’s such a bullshit answer but it is still so true.

Like Crazy is currently streaming on Netflix. Follow Drake Doremus at @drakedoremus.

Interview by Kelsey Barnes

Photographs courtesy of Drake Doremus